Sometimes you rub it with garlic and drizzle olive oil on it before spooning a thick layer of this shiny, lush red concoction on top. Sometimes you crumble salty white Sirene (сирене - a young salty cheese, like Feta), maybe a little hot pepper or green salt or more oil. You do this on the so-called most depressing day of the year - Blue Monday, or the third Monday in January. You are skint and a bit cold (in fact you skip the olive oil as it’s coagulated to near solid in the kitchen).

But when you lift the toast to your mouth, you get a rush of late summer, of the smoky flesh of blackened peppers, of tomatoes vibrating with flavour, with sunshine. You get the aftertaste of wood-roasted aubergine, of carrot, garlic, cumin and parsley. It’s all balanced by salt. Not quite enough salt, because your salt tolerance has gone up in the last few years of living here in Bulgaria. But Baba Radka was on a low-salt diet because of her recurrent breast cancer, and you didn’t want the lyutenitsa to turn out less healthy for her. You feel a jolt of happiness at the thought that the warmth and light is coming around again, that it won’t be this dark and grey forever.

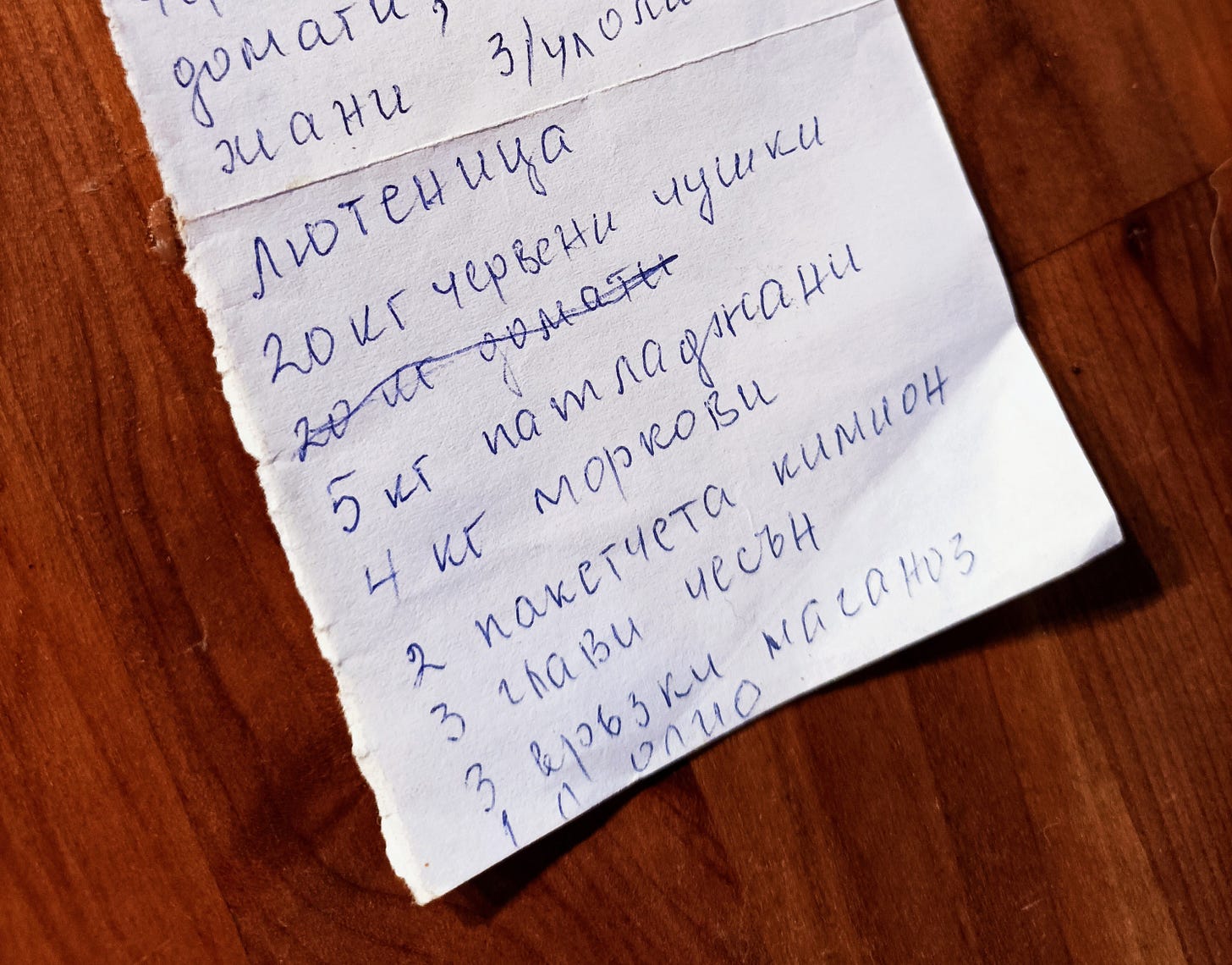

Last summer you didn’t make lyutenitsa because she was already dead by then, and you didn’t feel like growing all the tomatoes, or haggling for the peppers in sacks on the side of the road, because you never get the hang of growing the big red peppers yourself. Besides, you need tons of them - 20 kilos. Last summer you found the slip of paper you thought you’d lost, with her handwritten list of ingredients on, and you tuck it away inside the door of a cupboard.

What’s lyutenitsa (лютеница)?

It’s hope, in a jar. It’s a mixture of minced tomatoes fresh from the vine, of roasted peppers and aubergines (usually although it varies), and, and it’s almost always cooked outdoors. You don’t need a garden, even: pass any block of flats before the kids go back to school and you’ll smell it before you see it: the unmistakeable scent of whole red peppers cooked either on an improvised baking tray over a gas hob on the balcony, or in a special machine called a chuskopek (чушкопек - literally a pepper-baker) which you plug in and insert peppers in one or two or three at a time until their flesh goes soft and sweet and the skin is falling off. Listen to the gossip and laughter as women sit outside and peel the peppers, hands stained and sticky, little flecks of blackened pepper skin everywhere. Lyutenitsa is packed in suitcases by Bulgarians living abroad, stocked in Balkan grocers in damp northern countries. It’s just a necessity. It’s an act of love.

You think that this year, you’ll make the effort, you’ll use Radka’s recipe again, for joy (and her name means joy) and because this is the last jar. You remember how she adopted you as a stand-in daughter when you came to the village, how she’d phone you and ask you to buy chicken necks and bread if you were in town, how she said ‘maybe we can become like family’ and how you took her once or twice to jazz concerts in the park or to the gallery, and how she always wanted to see the Bosphorus but you weren’t brave enough to take her all the way there, not on your own.

You don’t want to exoticise her - a Bulgarian granny, smiling and happy in her cottage nestled in the foothills of the Balkan mountain. She was fierce and shrewd, a former engineer at the Arsenal arms factory in town. She bossed her husband around, liked listening to concerts loud on the TV. She was a bit bored in the village and had a wicked giggle. When you were going over the ingredients to buy, the ones not in your gardens, she called you silly for asking whether you needed to buy aubergine (patlazhan - патладжан) when she’d literally just told you to buy aubergine (sin domat - син домат or ‘blue’ tomato).

Still, you feel sad remembering her, how she went too soon, the blood in her veins not keeping up with the vitality in her mind. You miss your own mum over in the UK, who is almost the same age, who has hardly been able to come over the last few years with the pandemic.

Making the magic

Radka and her husband Georgy would roast most of the peppers themselves because I was busy, and they would sit out on their hot terrace peeling them and niggling at each other. Then I would arrive with all the other ingredients and my electric mincer, and we’d sit out behind their house with the wood fire burning and a long, ancient extension cord. The tomatoes and peeled peppers would be minced, not too finely because we liked it a bit chunky, and the carrots would be softening in a pan of boiling water. The giant cooking vat would be cleaned and oiled and hauled up on top of the fire, and we’d add all the red stuff and stir and stir with a wooden paddle. Then we’d mince the carrot and roasted aubergine and add that too, with more oil, and salt and cumin and black pepper. Not too soon, nearer the end, loads of garlic smashed and chopped small. Right at the end, the chopped parsley. The recipe said sugar but we wouldn’t add sugar because the tomatoes and peppers were so sweet already.

Then we’d spoon it into jars, already washed and warming in the oven, seal them while everything was still hot, and split the prize between us.

And then we’d be glad each time we opened a jar, each time we spooned the mixture onto toast, or next to grilled pork kebabs, or an omelette. Because we captured summer in a jar, and not just that - the force and wit of a woman called Radka.

I loved that - thanks. I've lived in Bulgaria for quite a few years and learned how to make all these wonderful things from my neighbours. I had lutenitsa on toast for lunch today....with a bit of stilton just to mix things up. I'm so glad I was here to see some of the little things about village life that are disappearing..... ploughing with the horse, the goats going out every day....loads more than are on my write about. Благодаря

Hi Jo. I enjoyed reading that. As you weave the love for the lutenitsa with the love for your neighbour is felt so familiar. All of us who live here, in any one of the villages know this combo so well. Thanks! We met once at an EKF thing in the Red House. I am on substack now, check out my recent piece on the village life. Would love to hear your thoughts. All the best, Chris